Feeling overwhelmed by “big data goals” for the new year? Relax: your 2026 data plan doesn’t need to be fancy, expensive, or AI-heavy to make a real difference. Here’s a totally doable data to-do list most nonprofits can actually complete.

1. Pick 5 metrics that matter (and drop the rest).

Choose a short list tied directly to decisions you make: participation, retention, outcomes, revenue, or reach. If a metric doesn’t inform action, it doesn’t make the list.

2. Create one shared data source.

Whether it’s a clean spreadsheet, Airtable, or database export, aim for one place your team agrees is the source of truth. Version chaos is not a data strategy.

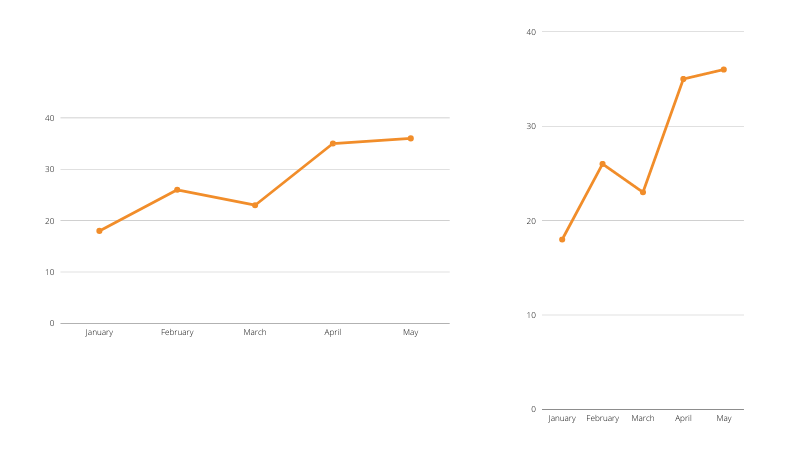

3. Build one reusable chart set.

Design 3–5 charts you can reuse all year—for board meetings, funders, and reports. Consistency saves time and builds trust. If you’d like help with this, check out ChartPacks.

4. Add plain-language takeaways to every chart.

One sentence is enough: “Participation increased after we added evening programs.”

5. Schedule a quarterly “data hour.”

Put it on the calendar now. Review what changed, what didn’t, and what surprised you. A simple data dashboard with real-time data is a great tool for this. If you’d like some help with this, let’s talk.

6. Use AI for the boring parts, not the thinking.

AI is great for cleaning data, fixing labels, summarizing trends, or drafting chart captions. Humans still decide what matters.

In 2026, progress isn’t about more data—it’s about clearer, calmer, more usable data. Small, consistent steps beat ambitious plans that never get finished.

Let’s talk about YOUR data!

Got the feeling that you and your colleagues would use your data more effectively if you could see it better? Data Viz for Nonprofits (DVN) can help you get the ball rolling with an interactive data dashboard and beautiful charts, maps, and graphs for your next presentation, report, proposal, or webpage. Through a short-term consultation, we can help you to clarify the questions you want to answer and goals you want to track. DVN then visualizes your data to address those questions and track those goals.