Charts, graphs, maps, and other types of data visualizations (aka “data viz”) often pull me in, especially if they are visually striking. But until I became versed in the art and science of data visualization, even dazzling charts often would frustrate me. I could not extract their meaning quickly and thus moved on.

There are five steps in quickly consuming a data viz. I know that doesn’t sound quick, but most steps take only seconds to do. In each step, you answer a simple question. The questions are:

1. What’s this about? What question is it answering?

This first question comes from a 1940 classic book called How To Read A Book by Mortimer J. Adler. Adler maintains that you don’t save time on books by learning to speed-read. Instead, you save time by making an informed decision about what to and what not to read. And the best way to make this decision is to do an “inspectional read” which means skimming through titles, headings, tables of context, etc. Similarly, when you encounter a chart, map, or graph in text, skim over it by reading the title and subtitle, and any captions or annotations. Then determine what its about and, more specifically, what question it is trying to answer.

2. What’s my guess about the answer to that question?

This might seem like an unnecessary step, but studies have shown that comprehension increases when a reader forms questions about a text before consuming it. A question primes your brain for an answer. The more our curiosity is piqued, the easier all learning becomes.

3. What’s the quality of the data?

This might be the most important step and the least likely to be taken. At least determine the source of the data and whether the source appears to be reliable and credible. True, individuals will disagree on which sources are reliable and credible. Some of us, however, might be wary of data from institutions with clear political leanings or agendas. If no data source is noted, the viz is not worth your time.

For extra credit, look for information on what is and what is NOT included in the data. Consider, for example, the time period of the data and the demographics of people represented by the data. You are trying to determine if the data are equal to the task of the visualization. Can it really answer its question(s)? Or are there gaps in the data that weaken its ability to answer the questions fully or at all?

4. What more can I learn from the structure of the viz

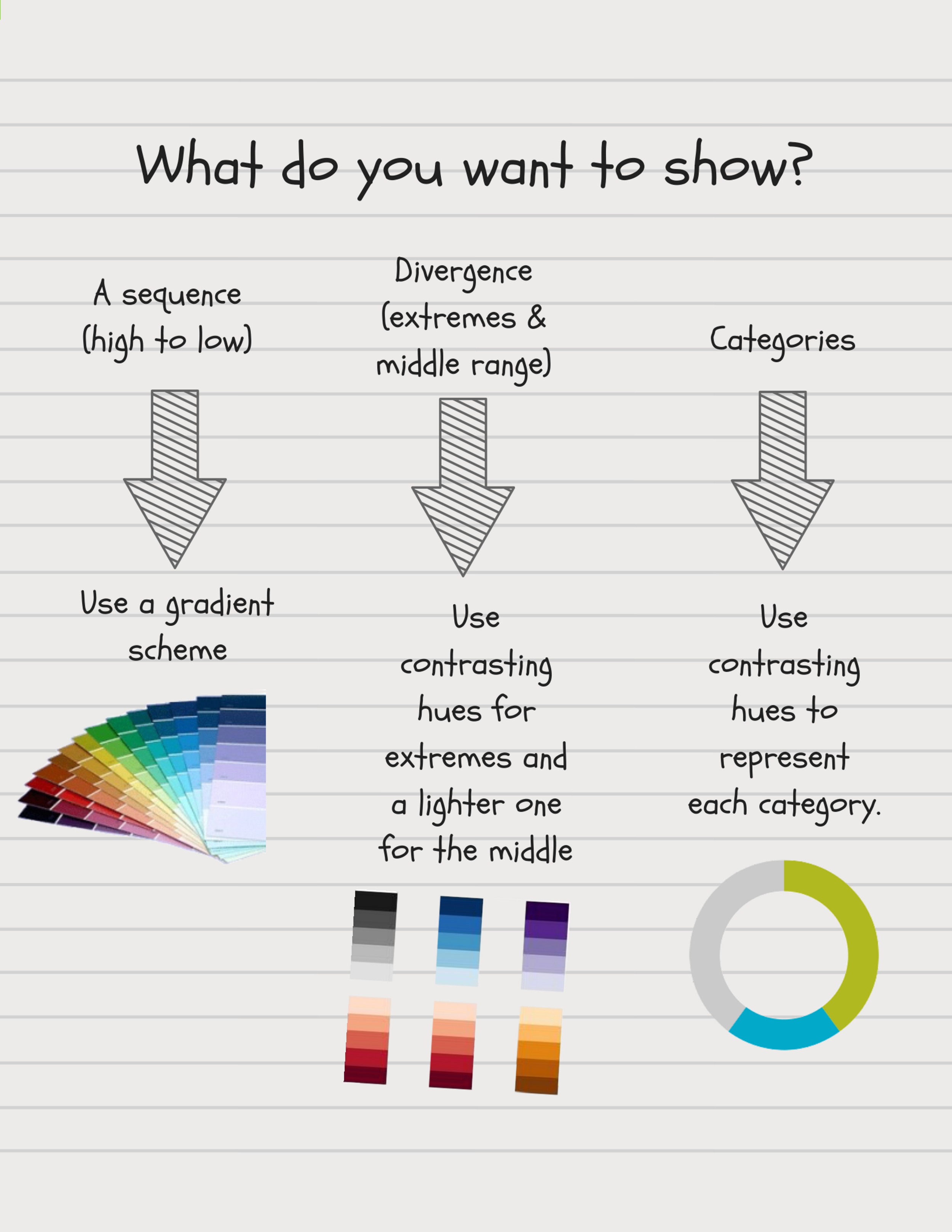

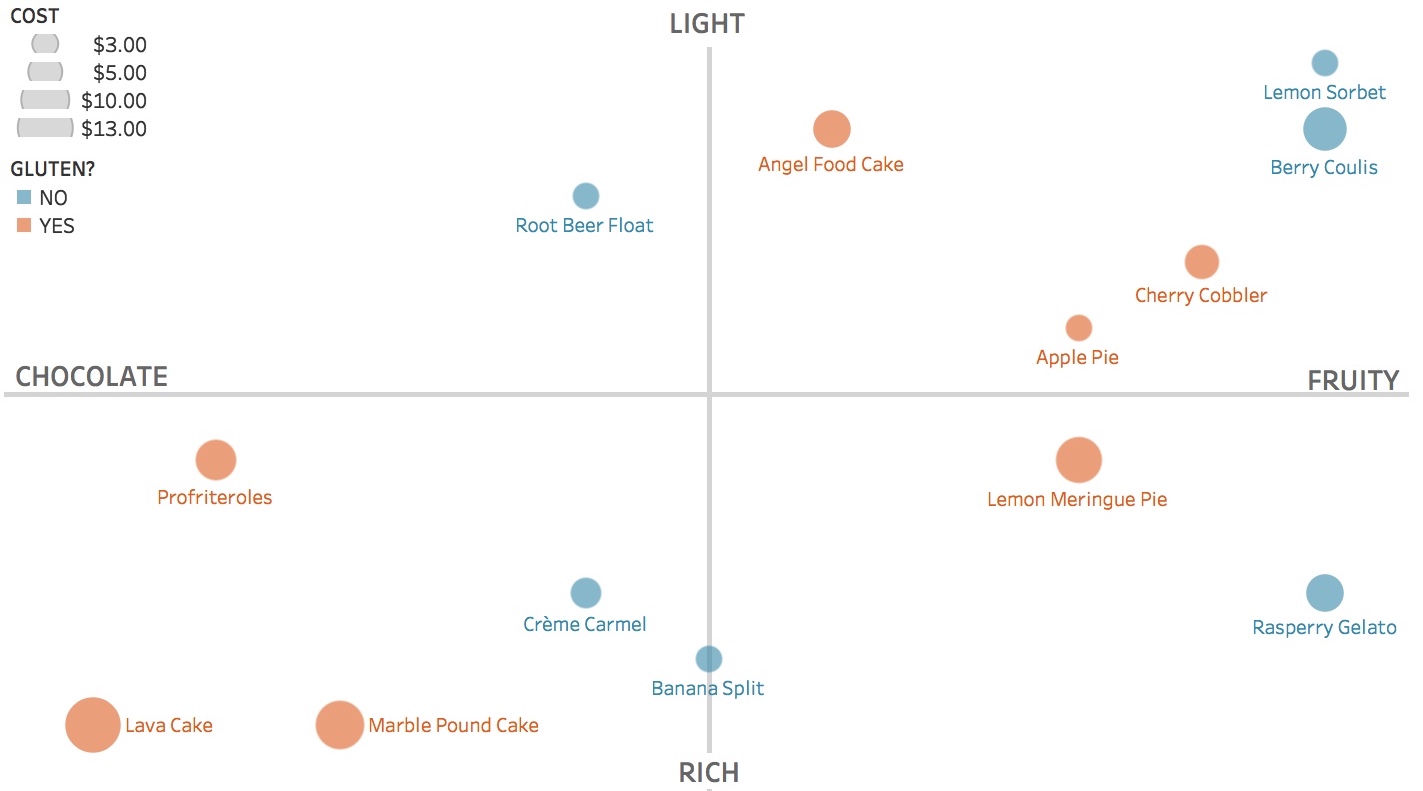

If you have gotten this far, you are engaged by the viz. Now consider what it all means. A visualization is, by nature, an abstraction of reality. It shows data collected in the real world using position, color, shape, and size to represent the data. Thus it’s important to understand what these visual cues mean in the particular viz you are consuming.

5. What is the answer to the question and what questions am I left with?

Finally, consider what answers you see in the viz and how they compared to your expectations. And to prime yourself to consider future information on the same subject, ask yourself what else you’d like to know about it.

See other data tips in this series for more information on how to effectively visualize and make good use of your organization's data.